California has some of the worst air quality in the country. The problem is rooted in the San Joaqui

FRESNO, Calif. — The ongoing effects of climate change have left much of the western United States to suffer from worsening air quality in recent years, with more than 40 percent of people in the country now living in places that earned failing grades for unhealthy levels of particle pollution or ozone, according to the American Lung Association.

But in places like California’s San Joaquin Valley, home to large productions of oil, agriculture and warehouse distribution, this has been the case for years. The region has been out of compliance with Environmental Protection Agency standards for 25 years, earning the region the unwanted distinction of being among the most polluted regions in the country, and residents and air quality activists say there have been few significant solutions. As California heads into another wildfire season, environmentalists and lawmakers are trying to revive a decades-long push to strengthen air quality regulation to curb pollution and reduce the many consequences of daily life with dirty air, including rising health care costs.

Clean air activists argue that the Valley’s air district hasn’t done enough to meet air standards because polluting industries in the region have been too influential in shaping policies around air quality and has contributed to the slow pace of cleaning up the air in the region.

During his time as an emergency room doctor between 2007 and 2015 in Selma, just outside Fresno, Dr. Joaquin Arambula remembers patients regularly seeking care for breathing problems. Visits increased when pollution levels spiked.

Now a representative for California’s 31st district in the state assembly, he recently introduced a new law that he hopes can help boost regulatory powers on air pollution across the state, and in his home region.

Read More: ‘You can’t just hold your breath.’ Toxic smoke, fueled by wildfires, chokes California

Assembly Bill 2550 would give greater power to the California Air Resources Board, which works with local air districts to prepare plans on combating air quality, to examine why local air quality plans fail and to bring in community groups to help strategize new ways to combat air pollution. The bill could come up for a vote in the state Senate by August.

The bill is symbolically numbered “2550” because it has been 25 years since the region has been in compliance with federal air standards. The goal, Arambula said, is to meet those air standards within 50 years.

“I believe we have to think outside the box and ask for more assistance from other regulators to help us to get into compliance,” Arambula told the NewsHour.

In April, the American Lung Association released its 23rd “State of the Air” report, which showed the number of days of “very unhealthy” or “hazardous” air rose to the highest level in two decades across the United States.

The report measured air quality between 2018 and 2020, which it noted were among the seven hottest years on record globally. Heat is a major contributor to ozone pollution, which happens when emissions react under heat and sunlight. Natural disasters like wildfires have also released hazardous fine particles into the air in California and other western states. The particles in smoke, known as PM 2.5, are tiny enough to enter the bloodstream and cause a number of health challenges. Particle pollution causes breathing problems of varying severity, including asthma attacks and COPD exacerbations, and even lung cancer, according to Laura Kate Bender, national assistant vice president of healthy air for the American Lung Association.

The Lung Association found that counties in California and several western states received failing grades for air quality despite states putting stronger emissions standards in place and cleaner vehicles being on the road. According to the association, the Fresno area ranked the highest in the nation this year for short-term air pollution; it replaced Fairbanks, Alaska. A hundred miles south, Bakersfield ranks the highest for year-round pollution. The report also notes the pollution disparities created by climate change, which are likely to grow through drought and heat events, and which are disproportionately affecting communities where majority Black and brown people live.

“Unless we take action to really address climate change, it’s going to undo a lot of the progress that we’ve made in the country in cleaning up the air,” Bender told the NewsHour.

Pollution: a local problem

Last year, communities around Fresno and Bakersfield were shrouded in ash and smoke from multiple wildfires burning in the state. Large wildfires have become a more common occurrence in recent years, making fighting local pollution more difficult.

Nationally, pollution levels have gone down ever since the Clean Air Act was passed in 1970, and subsequent amendments were passed in the 1990s. These targeted common pollutants like particles and ozone, among others. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, emissions from the most common pollutants dropped by 78 percent between 1970 and 2020 — and the agency estimates around 2 million premature deaths from asthma exacerbations related to air pollution were prevented.

The agency credits cleaner fuels and tougher regulations at the state level to lower emissions for the improved air quality. But while the federal law has had a wide-reaching impact, some places have seen slower change.

The EPA, which has approved only portions of air quality plans for the San Joaquin Valley in the past decades, has classified the valley as in “serious” or “extreme” non-compliance with pollution standards for ozone and fine particulate matter (PM 2.5), which at 2.5 microns or less in width can travel deep into a person’s respiratory tract.

A mail truck drives down a rural road in Kern County as a haze covers the Sierra Nevada mountains in the distance. Photo by Cresencio Rodriguez-Delgado/PBS NewsHour

To meet standards set by the EPA, state and local air regulators must submit detailed attainment plans to reach federal standards and must outline funding to reach those goals.

The EPA has routinely given California air officials extended deadlines to submit new plans due to shortfalls on things like funding or incomplete implementation plans in the Valley. It has even threatened to place sanctions on highway funding unless plans were submitted to show how the state would meet air standards. So far, none of those extreme actions have come through.

Frustrated over a decades-long battle to attain federal air standards, environmental groups last fall sued the EPA to pressure state agencies on taking tougher action against pollution. Similar lawsuits were filed as far back as 2001. Environmental groups have also accused air regulators of not being tough enough on polluting industries.

The San Joaquin Valley Air Pollution Control District, which oversees eight counties, has pumped $4.2 billion in public and private funding into clean air projects, according to a statement provided to the NewsHour by spokeswoman Jamie Holt.

Holt said the district has adopted more than 650 rules on air quality since 1992 and at least 212,000 tons of emissions have been reduced in that time. Holt acknowledged the district can’t control the issue alone, and the air district has tried to meet federal air regulations as best it can. Holt said the Valley continues to see population growth and also pointed to the growing challenges from wildfires, which – given the region’s geography – can trap smoke for long periods of time.

WATCH: How air pollution is disproportionately impacting minority communities in San Diego

“Meeting the latest federal ambient air quality standards will require significant additional emissions reductions from sources under local, state and federal jurisdiction, particularly with respect to mobile sources that now make up the majority of emissions in the San Joaquin Valley,” Holt said.

While the air district can’t control all the pollution coming into the region alone, there is interest in examining how the air district can better respond to the air crisis, similar to the approach taken by Arambula’s legislation.

Cade Cannedy, who graduated from Stanford University in 2021 and earned an award for his research on the Valley’s air quality, told the NewsHour that his research found strong interest in restructuring the way the Valley’s air district conducts its work.

He said California is “overrepresented in air quality problems, and underrepresented in successful outcomes,” which could be a result of local air districts facing the possibility of industry influencing which policies get passed.

Cannedy researched financial disclosures for members of air district boards, which are often made up of locally-elected officials, like supervisors or city council members. Cannedy’s research showed that of the 157 members of air quality boards in the San Joaquin Valley and South Coast, in Southern California, 37 were “demonstrably connected to the industries they were intended to regulate.”

Based on the research, he argues that “centralized, state-level regulation of air quality in California’s San Joaquin Valley is the only way significant progress on air quality will ever occur.”

“If you really want things to improve, you have to take power away from the polluting industries who are collaborating to stop progress on this front,” said Cannedy, who now works as a program manager for Bay Area-based group Climate Resilient Communities.

Holt, the spokeswoman for the air district, said board members who may have a conflicting financial interest on an air regulation are prohibited from participating in decision-making. She said officials on the board are required to submit a Statement of Economic Interest form which would disclose financial interests “to ensure officials are making decisions in the best interest of the public and not enhancing their personal finances.”

Despite its poor marks on air quality overall, Fresno has seen some improvement in recent years. A drop in ozone pollution helped the city move from third place to fourth place nationally this year. Between 2001 and 2003, Fresno averaged 217 high ozone days; a decade later, it averaged 60 high ozone days, according to the American Lung Association’s latest air report. Los Angeles remains the smoggiest region in the country. The significant cut to the number of high ozone days in cities like Fresno is a small reason to celebrate, Bender of the Lung Association said, but there is still much work ahead to curb pollution in the Valley.

“Not every community has seen the same level of cleanup,” Bender said. “There are a lot of cities and particular communities where people have been living by polluting sources for far too long and they’re still waiting for the benefits of the Clean Air Act.”

One estimate by medical researchers from California State University, Fullerton and Sonoma Technology from 2008 still widely accepted by air experts suggests that air pollution costs roughly $1,600 per person per year.

The Lung Association estimates that a full transition to zero-emission transportation and electricity could result in $1.2 trillion in public health benefits in addition to 110,000 lives saved by 2050.

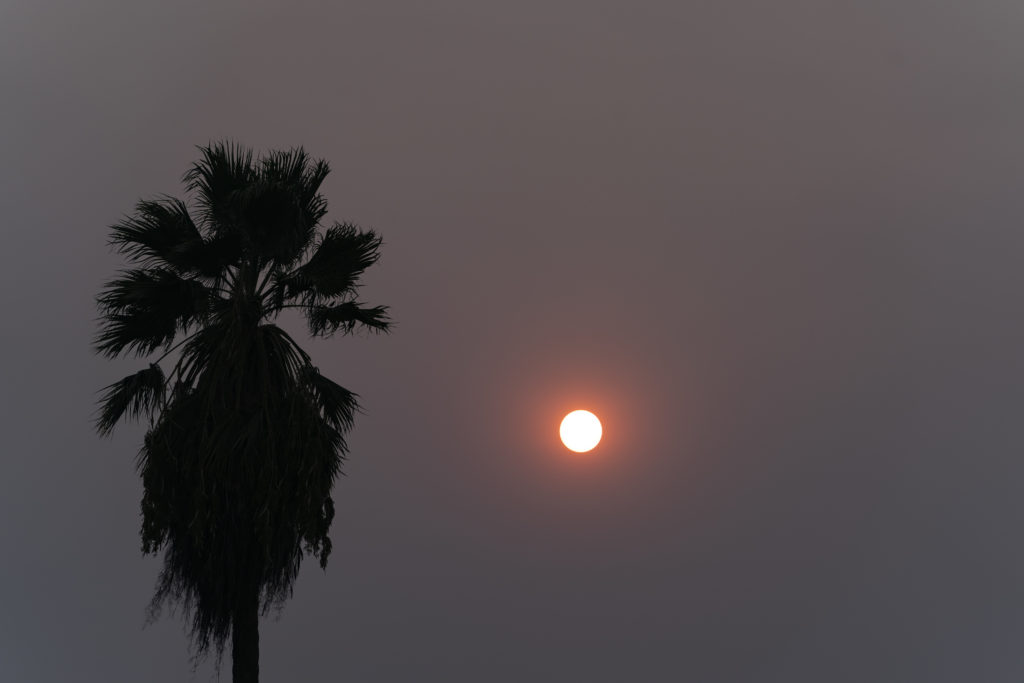

The sun, obscured by smoke from wildfires, as seen in Fresno, California. Photo by Alex Edelman/Bloomberg

‘Canaries in a coal mine’

It’s been nearly 20 years since retired journalist Mark Grossi and a team of writers released “Last Gasp,” a special news report in The Fresno Bee calling the San Joaquin Valley “the most dangerous place in the United States to breathe.”

The series of stories set out to inform the public about the way air quality worked, who and what contributed to it and who was in charge of regulating it. It chronicled stories of asthma, medical visits and the way geography and climate collude to create hazardous breathing conditions. The stories also provided information on what readers could do, including monitoring daily air quality.

All of those stories are relevant today, said Grossi, who remembers when most people didn’t think the Valley’s agriculture industry or dairy production had much to do with the air quality. He said information about air quality was difficult to find and break down.

“Everybody had a kid on the block that had asthma,” he said. “But it wasn’t really connected to anything, other than ‘that’s just the way it is.’”

Today, the direct and second-hand impacts agriculture production has on the air quality in the Valley is well documented, including the mixing of dust and vehicle emissions near communities.

The Lung Association’s latest report also hints at rising particulate matter pollution in the Fresno area. Between 2017 and 2019, days per year in the Fresno area when particles exceeded safe standards in a 24-hour period reached 34. Between 2018 and 2020 – a time that has seen heavy wildfires – the average number of high particle days reached 51. On these days, air officials will send warnings and residents are encouraged to reduce or avoid activities based on their risk levels.

Read More: Devastating heat wave in South Asia ‘sign of things to come’ in face of climate change

The team of researchers from California State University, Fullerton and Sonoma Technology have run models that would determine how much economic benefits there would be if federal air standards were met in the San Joaquin Valley. Poor air quality in the Valley typically leads to limited outdoor activities and the loss of work and school days in addition to a number of health issues; all of that carries a financial cost. Researchers, however, estimate under attainment of federal air standards for particulate matter and ozone, day-to-day impacts would be reduced and the region could save up to $5.73 billion annually that is otherwise lost to health treatment, as well as lost days for school and work from air quality.

Catherine Goroupa-White, executive director of the Central Valley Air Quality Coalition, has spent 16 years advocating for cleaner air in the Valley. She said the clash of problems facing residents related to pollution in the San Joaquin Valley has turned the region into an example of what happens when air regulation doesn’t go far enough.

“We’re like the proverbial canaries in the coal mine in the San Joaquin Valley,” she said. “We are the evidence of what our future is going to look like if these climate extremes persist.”

In 2021, environmental groups secured a victory after they convinced state air officials to phase out agricultural burning in the San Joaquin Valley; it had taken years of advocacy to get there. Agricultural burning involves burning fields that are no longer in production.

The open air fires are typically preceded by uprooting trees, then creating piles of waste which is then set on fire. While the burns typically happen in fields away from communities, wind carries smoke toward homes. The phase-out is set to be complete by 2024.

Goroupa-White said she has often answered questions from residents who wondered whether the pollution they experience in the Valley came from elsewhere, but she said she feels those questions are part of the misinformation that has existed about what contributes to pollution in the Valley.

“I still have people ask me all the time, ‘Oh, well isn’t it coming in from the Bay Area? Isn’t it blowing in from China? Isn’t it because you’re in a bowl? Isn’t it your geography?’” Goroupa White recounted to the NewsHour. “All of the excuses that the air district has as a narrative to explain away their responsibility, those are still persistent.”

ncG1vNJzZmivp6x7sa7SZ6arn1%2Bjsri%2Fx6isq2eelsGqu81ompqkmZu8s7rImmShmaNiwLC5xGamn2WknbJuw86rqq1lkZ6%2Fbr3UmqOirKlitq9506GcZpufqru1vthmq6GdXaW%2FsK7LnqRmoaNiv7C7056bZqGeYsGpsYysmKdlmqSussHIp2SvmZyhsro%3D